Mapping Crypto: The Minority Rule

June 19, 2019

Payments and privacy

Large markets are thought to serve the preferences of the masses. The minority rule is an asymmetric mechanism through which the preferences of a relatively small, intransigent minority can prevail. This climatic pattern can upset some common assumptions about payments.

Payments are networked and network effects favor the majority. The majority of the population is disinterested in matters of privacy, but private data is valuable. The result is that privacy-conscious individuals are robbed of agency through the indifference of the majority. This post explains how this dynamic can be reversed by leveraging the minority rule.

Soul in the game

Nassim Nicholas Taleb formulated the minority rule in Skin in the Game: It is enough for a geographically evenly distributed minority “with significant skin in the game (or, better, soul in the game) to reach a minutely small level […] for the entire population to have to submit to their preferences” if the cost of doing so is low enough.

Dietary restrictions may be the simplest example of the minority rule. The cost of making drinks kosher is relatively small as it only requires avoiding some additives according to Taleb, but it saves the trouble of custom branding. Since non-kosher eaters don’t mind the difference, the result is that most soft drinks are kosher in the US. Making all food products kosher would be much costlier, thus the minority rule doesn’t apply there.

The power of intransigence

Consider the scenario where a personal payment solution, Zebra, enjoys total adoption in the population. There exists a subset of the population that is strongly dissatisfied with Zebra due to privacy concerns. A new personal payment solution, Alpha, is introduced with provable privacy that builds on a new protocol. Members of the dissatisfied population immediately adopt the new solution and refuse to send or receive payments over Zebra. At the same time, they start advocating the use of Alpha and the power of intransigence in their respective social groups.

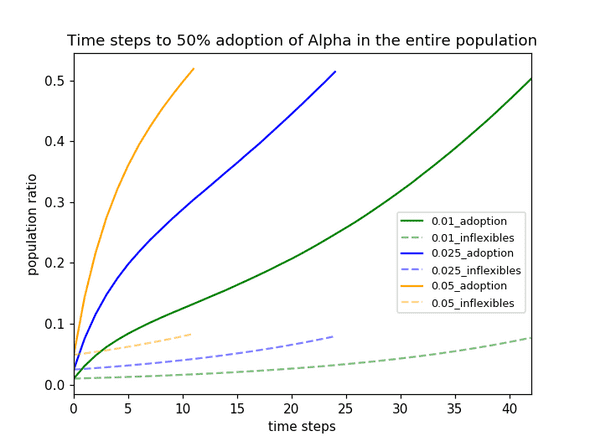

If the cost of switching to Alpha from Zebra is low enough, it suffices for less than 5% of the population to turn intransigent regarding privacy to drive the adoption of Alpha to a majority of the population within a few years (assuming a uniformly distributed dissatisfied population). The exact time depends on the size of the starting intransigent population and the assumptions made about the structure and dynamics of social behavior. Based on an exploratory simulation with what I believe to be conservative parameters, I found that given an initial intransigent population of 1%, Alpha is adopted by the majority within 3.5 years. With an initial intransigent population of 2.5%, it takes 2 years and with 5% it only takes 11 months (Fig 1). Methodology and results are detailed in this notebook. Code to run the simulation is available on GitHub.

Dynamics of the rule

The deciding factor in whether the minority rule can take effect is the cost of switching. To succeed, Alpha must provide an on-boarding experience that is as simple as installing a new messaging app. The cost of switching is the primary reason why the minority rule can’t take effect in consumer to merchant online payments, as the burden on merchants is too large. However, if Alpha reaches majority adoption for personal payments, that can be used as a bridgehead to enter online payments.

Another difference with online payments is the structure of interactions. Personal payments happen in small groups, where the voice of just one individual can drive the group to switch protocols, and once a group is converted, its members increase the probability of adoption in other groups as well. This dynamic greatly accelerates the speed of adoption, but there is no equivalent dynamic for online payments.

Providing adopters with a financial incentive to advocate its use was one of the great innovations of Bitcoin. This is a lever that Alpha can lean on to accelerate the growth of the intransigent population.

The Achilles heel of the minority rule is polarization. If multiple privacy focused personal payment solutions compete for the same intransigent population, the power of the rule is greatly diminished.

Finally, it must be noted that the minority rule is no silver bullet. Any payment solution expecting to leverage it must execute flawless context specific gameplay in order to succeed against an incumbent enjoying total adoption.